Interview & Introduction: Akatsuka Seijin

Interpreter & Text: Yamamoto Wataru

The following is the extended version of our interview with director Kelly Reichardt, published in the November 1st issue of “TIFF Times.” The interview took place on the morning of October 31st, at the Tokyo International Film Festival(TIFF) office in Tsukiji, just before the director returned to the United States.

Reichardt came to Japan to participate in a joint project of the 36th TIFF, the symposium, “120th Anniversary Ozu Yasujiro: ‘Shoulders of Giants’” (October 27th, Mitsukoshi theater). However, time was limited at the symposium, and she couldn’t fully express her thoughts on

Ozu’s work. So, we conducted an interview. Due to limited space in the daily paper, we could only provide a summary. But she had many more stories and thoughts to share.

Coinciding with the Japanese releases of First Cow(2019) and Showing Up(2022), we now present the full, nearly one-hour interview here. The entire TIFF Times team is delighted about this, and we express our gratitude to everyone who contributed to the web publication of this “special issue.”

Q: You came here to attend a symposium about Ozu Yasujiro. How was it?

As an American, it’s hard to talk to a Japanese audience about their most famous director. This is my first time here (Japan). So, I wanted to ask many questions. But I talked about Tokyo Story as a road film and compared it with themes of American road movies. Then I talked about the women moving, over the course of Ozu’s films, from a total victim, like in A Hen in The Wind, to being seemingly stronger and more outspoken. But still martyrs for the family from American eyes.

One question I asked was about, in his films, the men dropping their clothes on the floor and the women bending down to pick them up. Is Ozu showing this as a routine – the way he shows someone clipping their nails? Or is he making a statement about the roles of men and women? As an American, I can’t know.

Especially in the later films, say Equinox Flower and Late Autumn, and the ones where the language becomes so minimal and he’s repeating shots. Incredible. I mean, the same set up – in the office it’s the same, the actors are the same, the camera setups the same, themes are the same. But beautiful perfection. Nothing extra. And each one different. But the men have this obsession about who’s marrying their daughters. In America, the idea of men thinking about such a thing would be, especially in the time, that would be frivolous. Or much more a women’s sort of gossip kind of thing. So, it’s so interesting to see these men getting together and talking about marriage. But the women are standing by but come across as more knowing and sort of waiting for their husbands, who hold the power, to come around to what is easily evident to them. He reminds me of Max Ophüls and his themes. Really, he’s on the side of the women who sort of get to the answers without all the struggle that the men go through.

Q: Did you feel it was sexist when you saw those scenes with men dropping their clothes at home and women bending and picking them up?

Yeah. Even the impression I got talking about it the other night. I could be wrong, but you know, there’s a misogyny of course. The act of, “I’m dropping it on the floor, so you bend over,” is quite extreme.

Just the lowering, the constant bowing. Getting down on your knees to clean up after someone, is quite… In America… Well, those clothes would just stay on the floor (laughs). And so, I’m thinking that because Ozu is so… he loves his women actors. So, I’m thinking that he is saying something about the ridiculousness of that gesture. But I don’t know because I don’t know Japanese culture enough.

Q: It’s a pity that this topic was not discussed at the symposium. But it seems to me that Ozu directed those scenes as a series of movements of a married couple to show how well the couple gets along and knows each other. I am sure that many Japanese would feel the same way and it would unlikely that the Japanese who saw it when the film came out would have felt that the husband was insulting his wife. Regarding this, in an English edition of Hasumi Shiguéhiko’s “Directed by Ozu Yasujirō,” set to be published next spring, there’s a section called, “Changing Clothes,” which you’ll probably find interesting.

Regarding Ozu’s work from a female perspective, you mentioned earlier that they seem like “martyrs for the family.” Is there anything else you have noticed?

We watched Good Morning. And the gossiping women, they’re just stuck at home all day. But in Late Autumn, the women have jobs. The young women. And they’re going on a hiking trip, and they say, “I’m happy as I am.” They say it again and again when people are talking about marrying them off.

So, I have this feeling of like, you think that they’re saying that they’re happy as they are and living life being single is an option, instead of picking the clothes up off the floor. But ultimately, it’s not really a feminist statement. Because ultimately, they’re being in consideration for taking care of one of their parents. But I think maybe the idea of marriage and family is very different in our countries too.

One wonders what would have happened if Ozu had made films through the 60s to the 70s, when the women’s movement came along. I’m so curious.

Q: Did you have a chance to see any films at the festival other than Ozu’s?

I only went to Ozu every night. I’ve seen 16 of his films in total. Some before I came, just rewatching some, and here I saw four. My whole trip is around Ozu. I’m seeing Japan through… I’m seeing scenes on the street that remind me so much of Ozu films. Like, I saw a little girl, I think like three years old, and she’s walking on the street by herself. She’s in her own head, she’s wandering, and she doesn’t realize how far she’s gotten from her father and her brother, who’s maybe five. In America, the father would just yell. But he doesn’t yell. He just watches. And the little boy’s getting very anxious that she’s getting so far away, tugging on his father. And the father just waits. She gets quite far. And then she turns and sees how far away she is from them and just walks back. The cars are passing. And the brother is clearly relieved. And the father doesn’t scold her. He just takes her hand, and they walk on. That’s so Ozu, I thought! Beautiful.

Q: Did you learn something new about Ozu or Japan by coming here for the first time?

It seems to me the Japanese are more for the collective. And America is about the individual. And so, his films seem so careful to me.

But in life here, everyone is good at their job. Everyone, no matter what your job is, it seems people do it the best they can. Very… not like America. And just the detail of everything in Japan. The way everything works and is thought of. In the drawers… And the perfect little things you need.

Walking around sometimes, getting lost on the street, I’m overwhelmed. In Floating Weeds, I think it has some of the most beautiful images I’ve ever seen in my life. And then I’m walking on a street and… same beauty. And someone is leaving just their bicycle near the train, and it’s not locked. Just this collective.

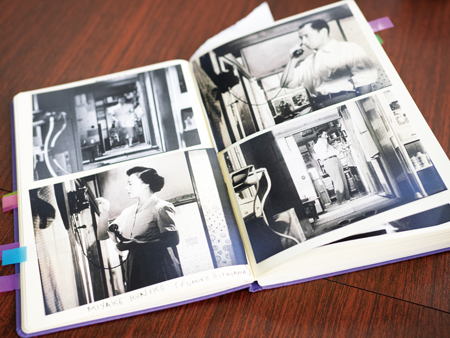

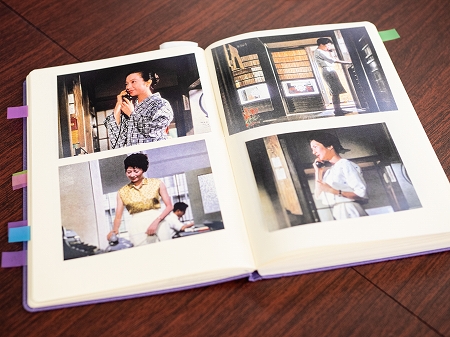

Q: I notice you have a notebook with bunch of photos and memos.

A cheat sheet! For this trip. I made this for the symposium. I thought the talk might be two hours, but it was two minutes. I was very nervous. But it’s okay.

I took so many Ozu photos. I was seeing and taking pictures really through his eyes. He’s always shooting in the corridor. In the alleyway. I see that everywhere. So beautiful.

Q: Let me ask you about your films now.

This will tie it in. Because my last film, has a lot of ceramics, I visited Kawai Kanjiro’s House, the ceramicist, and his studio in Kyoto. The huge kiln is in his house. It’s a beautiful place.

Q: Two of your latest films Showing Up and First Cow will be released theatrically in late December in Japan.

I think only one film showed one time in Japan. So, I don’t know how everybody knows them. I guess streaming?

Q: Yes. And also, there were retrospective screenings of your work in 2019 and 2020 and they were quite popular.

Oh really? I didn’t know. Great! I’m so happy for them to be released here. Because the last film, also I was thinking just about Ugetsu quite a lot. In First Cow, it was very much on my mind. So, it’s nice to play here. I think my biggest influences come from probably French and Japanese filmmakers. Japanese filmmakers like Ozu tell you, “It’s okay, you can take your time.” You can watch someone, and stillness is important. And Bresson tells you that too. Also, the characters always are very much a part of their place. Like the environment they’re in is very important and considered. With First Cow, there was Ugetsu, but also The Apu Trilogy – the Satyajit Ray films – were very important. Ozu is filming very low to the ground. And so, I was looking at films that shoot down low.

Q: You’ve been skeptical of this so-called “Barbenheimer” hype last summer. Why?

Only in one interview and the guy made it a big thing. But I didn’t see either film. I’m just tired of the push. Of the idea of mixing those two films together. And I think just the idea that… It’s a trying to sort of be everything, this film Barbie. So just speaking of the promotion. The idea that you can be working for a giant plastics toy company and be making art. It’s just silly to me. It’s nothing against the director. The promotion was just exhausting. And Americans, and I think maybe Japanese, too, love marketing. It must be strange to see the Oppenheimer phenomena from a Japanese point of view.

Q: In First Cow, you depict two societies. The indigenous world and the white one. Is this conscious? For you to —

This is to me what the film is about – and the writer that I work with, Jon Raymond. Yes, the conqueror, which is the trapping company that came to the Pacific Northwest and basically wiped out the indigenous communities. It’s the very beginning, but already there’s a class system. And in one scene, in the house of the head of the trappers, there’s a servant from Hawaii – the Sandwich Islands. There’s the Chinese man, a Native American wife… Well, Indian wife at that time. And so, between these tiers, there is a poor white man and a rich white man. And women. An Indian woman. So, this scene is about the pecking order. Before there’s even a currency yet, the first thing is a class system.