While anime in Japan always tended toward television series based on popular manga, there has been a recent surge in support for standalone feature films, many with increasingly realistic worlds. At a symposium on The Possibilities of Animation Expression, held on October 29 at the 36th Tokyo International Film Festival, several award-winning directors gathered to share their views on issues related to animated filmmaking.

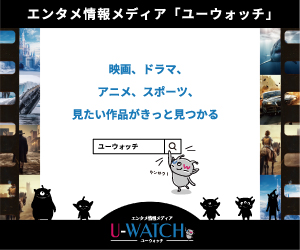

The directors, who all have films screening in this year’s revamped Animation Section —Hara Keiichi (Lonely Castle in the Mirror), Katabuchi Sunao (In this Corner (and Other Corners) of the World), Itazu Yoshimi (The Concierge), and Pablo Berger (Robot Dreams)—joined TIFF Programming Advisor Fujitsu Ryota on stage during the event for an illuminating discussion of the potential of their craft.

Hara cited his lack of experience as an animator as a strength, saying it allows him to draw inspiration freely from a range of anime, as well as from manga and live-action films. His films tend to conclude with emotional scenes of characters running toward something. The director said he often starts with such scenes in mind before creating the scripts and storyboards.

“Once those last scenes are in place, I am simply running toward that goal,” said Hara. “I then meet with the characters for the first time and they start to become more realistic and clear.”

Katabuchi also does not possess an animator background, though for 20 years he has taken the unusual step of using a device called a ‘quick-action recorder’ to confirm and control the movement of drawings, all of which are still drawn at first on paper with pencil, which he then shares with his staff.

A trailer for the director’s new film set during the Heian period, The Mourning Children, was shown to a captivated audience. To create the film, Katabuchi explained how he had created a studio, Contrail, that brought in new animators to work alongside and learn from experienced veterans. The discussions between staff were productive, often focusing on how people lived 1,000 years ago.

“We tried to understand how people in the Heian era lived or what kind of sandals they wore that would affect the way they walk or other kinds of movements,” explained the director.

Unlike the others in the symposium, Itazu has had a respected career as an animator, and he drew on this background for his debut feature, The Concierge, which he said was meant to evoke Toei Animation’s animated feature films from the 1960s.

When giving instructions to animators, Itazu said his direction varied from scene to scene, with some scenes emphasizing a strong sense of realism and detail, while other scenes were more “manga-like” and fantastical, an approach that the director said is based on his own understanding of animation.

“When we draw, we have to confirm how something moves in reality,” explained Itazu. “We then abstract this and have fun making it our own.”

Berger has had a long and successful career directing live-action films, and the Spanish-French Robot Dreams is his first animated feature. Claiming he was here to “learn from the masters,” the director also revealed his process of adapting Sara Varon’s graphic novel of the same name.

As he was not an animator, Berger said he relied on animation director Benoit Féroumont’s guidance. Berger compared the process of finding the requisite animation staff to the plot of a Kurosawa Akira jidaigeki classic.

“It was a little bit like Seven Samurai,” explained the director. “We needed a great samurai, like Benoit, and he would make great animators out of those with less experience.”

Many of the directors had strong thoughts on the differences between live action and animation production.

Hara said that the best part of live action is that work is finished according to schedule. “It might seem obvious,” he clarified, “but because we book actors or crew for a set period of time, we pack the schedule and get everything done in a certain time period.” While productions might also be restricted by shooting windows or fluctuations in the weather, everyone is rushing to finish the work in a short amount of time.

On the flip side, Hara said, schedules in animation seem to “stretch endlessly.” This is a problem within the entire industry, but big hits tend to make people forget about the need for larger structural changes.

Scheduling issues have led to industry workarounds, like creating layouts and backgrounds with 3D, but this also produces collateral problems.

“Young animators don’t know how to create layouts now,” decried Hara. “An animator’s job isn’t just to draw characters, but how the character is situated within the layout.”

Itazu expounded: “Animators need to really understand what a shot is intended to convey.

They need to carefully read the storyboard and translate its impressions.”

Katabuchi concurred that the number of animators who can do that are indeed limited. “But if we can increase the number of people who can do that,” he said, “and encourage their ability to do that, it will help them realize the joy and appeal of animation. In our studio, we don’t use tablets, we use paper; we want animators to feel they are creating drawings.”

The directors’ frank discussion about animator training and learning the basics echoes contemporary concerns about AI and automation in art.

Hara said this lack of awareness and appreciation for art manifested in a humorous incident on his last film, where staff were ogling some new drawings that master animator Inoue Toshiyuki had drawn on paper when he arrived at work that morning. “It’s paper!” Hara exclaimed. “Why are you all touching it with your filthy hands before I get a chance to see it first?”

Berger said Japan’s continued production of 2D hand-drawn animation is “very special,” considering that most animation produced now in the US and Europe is 3D/CG. Robot Dreams was made as an “homage” to the Japanese tradition, he said, with every frame intended to “look like it was done by a comic-book artist.”

All four directors specialize in creating spaces that convey a certain reality, from the buildings of Edo Japan or 1940s Kuré in Miss Hokusai or In This Corner of the World, to the floors of a department store in The Concierge and the streets of 1980s New York in Robot Dreams. Itazu described this process as creating a “direct lie,” where animators rely on a mix of detail and ambiguity to give audiences the impression of a large but specific place.

Part of the difficulty for many of the directors in creating real places is that many of their works relate to past places that no longer exist and, in some cases, have sparse or unreliable documentation, such as for Edo-era Japan (1603-1868).

“Ukiyoé woodblock prints are so irresponsible,” complained Hara. Western realistic perspective was not present in Japan during this period, explained Itazu, so much of the art representing life is highly distorted. “It would have been nice if one person depicted the setting accurately,” lamented Hara, who said he looked at various historical depictions of Ryogoku Bridge for Miss Hokusai but found that all of them were radically different.

Katabuchi said that this emphasis on distortion might be a characteristic of Japanese art. “The emaki picture scrolls of the Heian period are similarly not accurate at all,” he said. “Starting from this period, we can see a history of deformation.”

Despite long careers in filmmaking and animation, all of the directors believe animated filmmaking has continued potential for new forms of expression. Katabuchi, for example, said that animation director Ando Masashi was continuing to push the envelope for animated detail with the new film they are working on together.

Hara cautioned that while 3D technologies were making background generation and certain types of shots easier to produce, he hoped young animators would continue to attempt to create new types of expression that took advantage of animation’s unique properties.

Berger said its appeal lay in its hand-drawn origins, and that even new forms of popular animation —like Sony’s Spiderverse films—used CG technology to mimic 2D form. He quoted Guillermo del Toro to emphasize animation’s versatility: “Animation is not a genre; it is a medium.”

Itazu argued that the core of animation lay in its “physicality.” Someone who draws a lot absorbs that, digests it, and processes it into drawings. This, he argues, is what creates the pleasant feelings we get when we watch animation. Katabuchi likened this act to “pantomime,” while Berger said it’s more like “magic.”

“Like the circus, we want to awe the audience,” said Berger.

Hara said there are certain scenes from anime that he remembers watching from his childhood, such as a shot in one episode of Star of the Giants of a player hitting a homerun. The day after that episode aired, everyone was mimicking the at-bat stance at school. Itazu said that while the scene is parodied now, it felt fresh and realistic to schoolkids at the time.

“Animation is the joy of mimicry,” Itazu concluded. “Even if we don’t know who or what is being mimicked, we might say to ourselves, ‘I can imagine that!’ Animation is and will continue to be good at this.”

Symposium: The Possibilities of Animation Expression

Guests: Hara Keiichi (Director), Itazu Yoshimi (Director), Katabuchi Sunao (Director), Pablo Berger (Director)

Moderator: Fujitsu Ryota (Tokyo International Film Festival programming Advisor / Animation Critic)