Though nominally a Chilean film, The Settlers, screened in the Competition section of the 36th Tokyo International Film Festival on October 28, is a truly international production, and not only because the producers represent a wide ranges of nationalities. “We had actors from all over the world, as well as the crew,” said France-based Chilean director Felipe Gálvez during the post-screening Q&A, “and we showed them the screenplay for feedback, because the story was universal.”

The story is centered on 19th century colonialism and takes place chiefly in the Tierra del Fuego region of Chile and Argentina. In 1901, this vast area, which includes wide plains and towering peaks in the Andes, was controlled by one oligarch (Alfredo Castro), a sheep rancher of European extraction who despises the native Indio culture because it does not recognize private property. This “king of the white gold,” as he’s referred to by the locals, dispatches a team of three men—a disgraced Scottish expat officer (Mark Stanley), an American tracker-cowboy (Benjamin Westfall), and a “mestizo” (half-breed) named Segundo (Camilo Arancibia) to chart a path to the Atlantic Ocean for his sheep. Along the way they are tasked with killing as many Indians as possible.

According to Gálvez, this tale of rampant genocide has been hidden from the world for the last century, owing mainly to the Chilean authorities. “It took nine years to make The Settlers,” he said. “and the last of the many countries that invested in the production was Chile, which really didn’t want this story told. It’s only been recently that the government has owned up to the massacres that took place at the time. But I think this is a universal issue, and that we should all talk about it. One of my purposes is to counter the Western propaganda that has justified the wiping out of native peoples.”

The film takes a provocatively varied viewpoint. Though we mostly see the action through the eyes of Segundo, we hear the opinions of both the Scots officer, MacLennan, and the Texasn cowboy, Bill. Though these two men are continually at each other’s throats, they hold attitudes that similarly justify the oppression of native peoples. For MacLennan, who is basically a mercenary, it is all about power; while for Bill it is mostly about accommodation. But in any case, they do what they’re told, and kill and rape the Indians they encounter without compunction.

Segundo, of course, is conflicted, but he has a practical outcome in mind: He will use the money he earns to buy a horse and return to his home on an island off the coast of Chile. But that means he has to participate in the killings, and he is not prepared to at first.

“The film is critical of many things,” Gálvez told the audience. “The political issues at hand have many layers, and one of the criticisms I tried to make was toward film culture itself, which has justified these kinds of actions over the years.” In the end, the movie takes a gradual turn away from the descriptive toward the polemical, with a representative of the government in Santiago visiting the oligarch in order to gain his assistance in a program to cover up the genocide so that Chile can open up to the world and “develop.”

The last scene, in which a native woman, Kiepja (Mishell Guaña), now married to Segundo and renamed Rosa, refuses to do what the government operative tells her to do for a propaganda film, made a huge impression on one audience member, who asked why that might be.

“Rosa represents defiance to the authorities’ attitude toward minorities,” said Gálvez in response. “Her husband, though a mestizo, was a criminal accomplice in the genocide, thus making her in turn an accomplice as well. So I zoomed in on her as she refused the government man’s request. On the page, this scene was very simple, but on the screen it is very powerful, and that’s to the credit of the actor herself.”

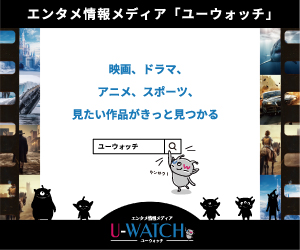

Q&A Session: Competition

The Settlers

Guest: Felipe Gálvez (Director/Screenplay)