This year marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of Ozu Yasujiro, generally recognized the world over as one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. To mark the occasion, the 36th Tokyo International Film Festival has been presenting a range of programs dedicated to Ozu’s life and work, including a section screening nearly all his extant films digitally restored in the 4K format; screenings of three new Ozu films reimagined by upcoming Japanese directors; and a symposium called Shoulders of Giants that took place on October 27.

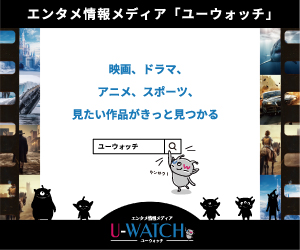

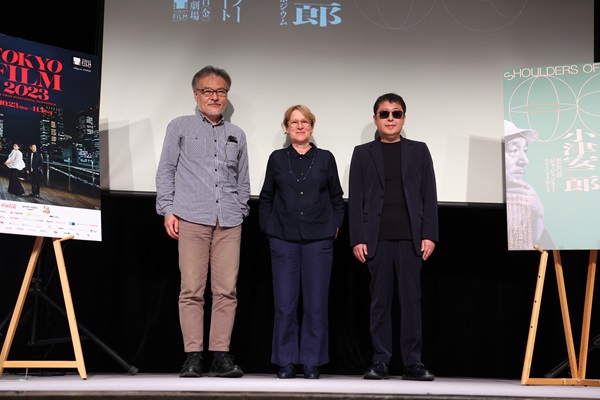

On hand to discuss the auteur’s ongoing influence and their own favorite films were three internationally renowned filmmakers, Japan’s Kurosawa Kiyoshi (Tokyo Sonata, Wife of a Spy), China’s Jia Zhangke (Mountains May Depart, Ash Is Purest White) and American Kelly Reichardt (Wendy and Lucy, First Cow).

But first, the president of this year’s TIFF Competition jury and Ozu aficionado Wim Wenders took the stage to greet the full-house audience and deliver opening remarks at the symposium prior to a screening of his own favorite Ozu film, Ohayo (Good Morning). Admitting that he wasn’t really prepared to say “something substantial,” he promised to record and share his thoughts later. Symposium moderator and TIFF Programming Director Ichiyama Shozo added that Wender’s statement would be uploaded on the TIFF YouTube channel at a later date.

Ohayo, made in 1959, was Ozu’s second color film, a loose remake of his earlier silent comedy, I Was Born, But… (1932). Updating the story to accommodate the emergence of Japan’s postwar consumer culture, Ozu sets the film in a suburban Tokyo neighborhood of single-story rowhouses on the Tama River. Much of the story centers on petty resentments, especially those engendered by community gossip about the disappearance of dues collected for the neighborhood association. There is also one couple who give off a more bohemian vibe, and the neighbors think the wife may even be a cabaret singer.

One family, the Hayashis, are scandalized when they discover that their two sons are hanging out with the couple to watch sumo on their TV, which was still a luxury purchase at the time. When their parents forbid them from going to the couple’s house, the two boys demand that they buy them a TV and throw a fit, refusing to talk. Conversing with adults is pointless, they say, since all they do is trade empty pleasantries like “Good morning,” and “Nice weather, isn’t it?” The boy’s silent treatment of everybody in the neighborhood only exacerbates the inter-household frictions, but in a comical way.

Following the screening, the three directors took to the stage and shared their reactions to the movie. Kurosawa said it had been years since he last saw it and was particularly impressed with how the 4K restoration “brought out the visuals and the specifics of the location shooting” (Ozu rarely shot films on location). Yet he noted that all the characteristics of Ozu’s style were there in abundance—the static compositions, the well-planned structure—and added to the comic mood. “It really brought out the misunderstandings between the characters, and was thrilling in that way.”

Reichardt, one of America’s most acclaimed independent filmmakers, said the movie reminded her of Douglas Sirk, the German emigré who made a series of Technicolor melodramas for Hollywood in the 1950s that have only grown in influence in the past several decades. “It’s those perfect colors and compositions and the setting, as if [Ozu] had painted each frame. And the attention to the minutiae of life—no heroes, just two boys who want a TV. Very beautiful.”

Jia, the representative filmmaker of China’s so-called Sixth Generation, said he studied Ozu extensively when he was at the Beijing Film Academy, and always identified with the two boys in Ohayo. “As a child in the 1970s I wanted a TV, too, and since China was about 20 years behind Japan economically, I could see their point. And while I always associate Ozu with family themes, this one is different in some way, because of the technology of the TV. Now we are in the age of AI, and if Ozu were still alive, he probably would have made this movie with a robot in the home.”

Each director had been asked beforehand to choose their favorite Ozu work and elaborate on it. Kurosawa chose The Munekata Sisters (1950), which he felt most people outside of Japan, even those familiar with Ozu, probably didn’t know much about. To Kurosawa, the significance of Ozu’s work following the war was how it charted the “disassembly” of the traditional Japanese family, an opinion he ventured would probably surprise many people, since Ozu is often considered to be the most consistent cinematic anthropologist of the mores and peccadilloes of Japanese domestic life.

“The Munekata Sisters is a central work in this disassembly,” said Kurosawa. “The characters refuse to understand one another—the younger sister is modern and the older sister more old-fashioned, and they never agree on anything. The father, played by Ryu Chishu, is always there but can’t resolve these problems. There’s a dark side here that I don’t remember seeing in other films from that time. The married couples don’t talk to each other. The wife, played by Tanaka Kinuyo, runs a cafe, and her husband gets angry and practically destroys it, demanding a divorce. He then slaps his wife seven times, and the younger sister comes after him with an ax. I love that scene. Ozu was trying to show how a couple can be violent, something you never saw in movies in those days.”

On a roll, Kurosawa then dived into the earlier A Hen in the Wind (1948), about a woman, also played by Tanaka, who becomes a prostitute for one night to pay off a medical bill while her husband remains missing in action after the war. When the husband finally returns, he can’t tolerate what she’s done and becomes violent, resulting in one of the most shocking scenes in postwar Japanese cinema.

Afterwards, Ozu settled back into his trademark ordered style, but Kurosawa thinks he retained this cynical attitude in his later, more famous work. “These characters didn’t forget the war,” he said. “There was still violence inside of them, which means he couldn’t forget the war, either.”

TIFF Programming Director Ichiyama Shozo commented that The Munekata Sisters, a restored version of which he recently saw at Cannes, was made for Shintoho, rather than Ozu’s usual studio, Shochiku, so maybe “there was no one there to rein him in.”

Jia chose Late Spring (1949), one of the last Ozu films he saw when he was studying to be a filmmaker and the first one to feature actor Hara Setsuko, who would become inextricably linked to Ozu’s later work. “What interested me about Ozu’s films was how they charted the changes in the Japanese economy in a clever way. The country’s rapid industrialization had a profound impact on the family. There’s that scene where the son brings his mother to Tokyo and shows her all the tall buildings. It showed that change was happening, and how human beings were adapting to that change.”

In essence, these changes are expressed personally through negative emotions—disappointment, sadness. The central relationship between the father and daughter is one of codependency, a situation that almost always leads to some kind of rupture. He continued, “The widowed father wants his daughter to marry and so he pretends that he will get remarried himself. When the daughter marries, he ends up being alone. The warmth of the family is not enough anymore. This movie was telling young people what modern life is about, and is very powerful in that way.”

The aesthetic Ozu pursued in Late Spring, according to Jia, proved to the budding filmmaker that cinema was distinct from literature. “Detailing the everyday is sometimes impossible using only words,” he explained. “Ozu goes beyond language, and I saw that in Ohayo as well.” Jia said that Ozu’s diaries were published in China two years ago, and he was surprised to discover how “westernized” he was. “There were many things there I didn’t know about Ozu, but what came through was how he always seemed to see beyond the contemporary situation. He had something to say to future generations, and still does.”

For Reichardt, whose own films owe much to Ozu’s compositional style, her first-ever trip to Japan had been eye opening, since she had always pictured the country through Ozu’s lens. In particular, she said she finds Ozu’s “obsession” with marriage indelible, which is why she chose Tokyo Story as her favorite. “To me, it’s a road movie, and in the US road movies are about existential discovery of one’s self, which tends to be rooted to a family that holds you down. So you take to the road to find out who you really are.” But the trip the elderly couple make to see their children in Tokyo is mind-altering in a different way.

What has always fascinated Reichardt about Ozu’s most famous film is the way the usual tropes of the road movie are reversed. “You aren’t looking out the window of a vehicle at the passing landscape,” she said. “Instead, you are outside looking at a passing train.” In Ozu’s films, there is no search for a new identity, but rather an attempt to confirm the identity one has always had. “That’s very un-American,” said Reichardt. “Dissatisfaction with one’s lot is the motivating factor in so many American films. That’s not the struggle here. The parents go to Tokyo and visit the ocean. There are big shots of them against the background of the sea, and they look out of place, because they want to be back home. That’s a very strange thing for a road movie to express.”

Reichardt admitted that she got to know Ozu backwards—starting from the later films and moving anti-chronologically through his filmography. “What blew me away was how much he could express through the same kinds of shots and the same actors sitting on the floor and talking about the exact same things. Now I’ve had the chance to see his earliest, much busier films, and I was impressed at how much he actually got rid of.”

Referring to Kurosawa’s discussion of the violent, darker side of Ozu, Reichardt commented, “What gets me [in A Hen in the Wind] is how, after she’s pushed down the stairs, the wife comes crawling back to beg her husband to take her back. To all the women in his films, marriage is a sacrifice. You see a man throw his clothes on the floor and the woman picking them up. That seems like a profound comment on marriage, but it’s hard for me to know for sure.”

Kurosawa responded by saying, “I think Ozu was actually making fun of that situation [with the clothes]. He’s saying that men are stupid. The husband who throws his wife down the stairs went to war and everyone thought he was dead. Maybe in a sense he was.”

“It’s just that it happens in so many of his films,” said Reichardt. “It’s like he shows the men as being hapless and the women as just waiting for everyone else to see what they see.”

120th Anniversary Ozu Yasujiro Commemorative Symposium: Shoulders of Giants

Moderator: Chris Tomoko (J-WAVE Personality).

Panelists: Wim Wenders (Filmmaker / 36th TIFF International Competition Jury President), Kurosawa Kiyoshi (Filmmaker), Jia Zhangke (Filmmaker), Kelly Reichardt (Filmmaker), Ichiyama Shozo (TIFF Programming Director)